[Event Report] The 136th HGPI Seminar “Where We Are Now and Where We Are Going Regarding PPI in Mental Health Research: Learning from the TOGETHER Project in the Form of Co-Creation” (July 28, 2025)

date : 10/21/2025

Tags: HGPI Seminar, Mental Health

![[Event Report] The 136th HGPI Seminar “Where We Are Now and Where We Are Going Regarding PPI in Mental Health Research: Learning from the TOGETHER Project in the Form of Co-Creation” (July 28, 2025)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/hs136-top.png)

The 136th HGPI Seminar featured a presentation by Dr. Takuma Shiozawa, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing at the Institute of Science Tokyo. Dr. Shiozawa, also a member of the “TOGETHER Project” that promotes patient and public involvement (PPI) in the field of mental health in Japan, spoke about the current state and future outlook of PPI in mental health research, based on the challenges identified and practical experience gained from his research.

<POINTS>

- Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) is becoming increasingly important internationally in mental health research, not only for protecting the rights of individuals but also for contributing to advancement of research.

- The benefits of PPI are diverse, with the potential to improve the quality of research at all stages, from the initial planning to the dissemination of results.

- However, challenges relating to the advancement of PPI in Japan still exist, including the power dynamics between professionals/researchers and individuals/families, the need to adopt a language that accessible and comprehensive for among all of them, and the issue of “representativeness” regarding who to collaborate with.

- The TOGETHER Project conducted a Delphi study to identify the most important outcome domains for community mental health research in Japan. The study involved stakeholders from various backgrounds, including individuals with lived experience, families, support professionals, government officials, and researchers. The project achieved an internationally high response rate of 93.6%, and consensus was attained on 24 key outcome domains.

- Although the Delphi study revealed differences in how stakeholders from different backgrounds rated the importance of the outcome domains, a set of items considered important across all groups was identified.

- Further research is being conducted to determine specific evaluation metrics for the consented core outcome domains, positioning this project as a pioneering example of patient and public-involved research in the Japanese mental health sector.

■ The Importance and Historical Context of Patient and Public Involvement in Mental Health Research

In the 1950s and 1960s, the field of mental health research was underdeveloped. At the time, mental health treatment often involved lobotomies and long-term hospitalization or institutionalization, which led to significant human rights abuses. Due to the lack of evidence-based practices, individuals with mental illnesses suffered greatly from inhumane treatment .

Following the advent of pharmacotherapy, the focus shifted to a human rights approach in the 1970s, which led to the promotion of the “right to know’ movement. Leading to the spread of informed consent, this increased the recognition of research as a way for professionals to demonstrate the effectiveness of their treatments and support services.

However, despite over half a century of research and massive investment, the effectiveness of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies for mental disorders is suggested to have limitations. Some research has revealed that current treatment and treatment-centered research has an upper limit on effectiveness and that a fundamental shift in thinking, or a “paradigm shift” in research, is essential for further progress. Stagnation in scientific development has also been noted recently, with a lack of diversity among researchers cited as a contributing factor. This highlights the necessity of involving people from various backgrounds in scientific advancement.

Based on the principle of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “Nothing about us without us,” individuals with lived experience have begun actively participating in research and other fields. This has increased expectations for patient and public involvement (PPI) to protect their rights and contribute to research development.

■ The Concepts, Benefits, and Challenges of PPI/Co-production

Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) is defined as “research carried out with or by patients and the public,” rather than “research for, about, or to the public.” This means that patients and the public are actively involved from the initial planning stages to implementation and publication of results. For instance, there are reported cases where patients and their families have participated in creating treatment guidelines in oncology.

PPI has varying degrees of involvement, from the consultative model, where opinions are simply heard, to the collaborative model, where patients actively cooperate in research, and the user-led model, where individuals with lived experience lead the research themselves.

Furthermore, co-production is an approach where “researchers, practitioners, and individuals (public) work together and share responsibilities from the beginning to the end of a research project, including opportunities to co-create and for mutual learning..” The momentum for PPI/co-production in research has been growing in recent years, with reports indicating that the number of studies involving patients and the general public in healthcare increased five-fold in the 2010s compared to the previous decade, and the emergence of articles requiring authors to describe their PPI efforts when submitting their manuscripts. In Japan, the implementation of PPI is becoming a standard for conducting research. In Japan, PPI guidelines and guidance prepared by patient groups to promote PPI have also emerged, attracting the attention of a diverse range of people and further expanding the scope of PPI in the country.

The benefits of PPI and/or Co-production are extensive. In the planning phase, it helps set research questions that are relevant to real-life issues faced by individuals, thereby improving the study’s overall relevance. Regarding the research methodology , it facilitates the creation of materials that are easier for participants to understand and promotes ethical considerations. For example, a patient’s perspective can help identify improvements in the wording of survey questions that an expert may miss. This can lead to increased participation and enrollment rates.

Regarding the analysis and interpretation of results, a multi-faceted perspective from the patient’s point of view becomes possible, clarifying aspects that researchers might have overlooked. Additionally, when disseminating research findings, it enables communication through methods and media that are familiar to individuals and leverages patient and family networks for information sharing. PPI also provides opportunities for growth for both researchers and participants. Participants become empowered , gain self-confidence, and acquire research skills, while researchers deepen their understanding of their field and the reality facing people with lived experience, and they learn to build better relationships with the community.

On the other hand, there are key considerations when implementing PPI.

- Power dynamics: A power imbalance can exist between individuals/families and professionals/researchers. PPI has the potential to transform existing systems and research methods, fostering research led by person with lived experience and their families. However, since “PPI in research” is often initiated and conducted within the domain of researchers and supporters, the existing power dynamic (e.g., doctor-patient relationship) can be projected onto the research setting, potentially making it difficult for individuals with lived experience to speak up. Continuous effort is needed to build a mutual relationship in which both people with lived experience and researchers can learn from each other. Experiential knowledge: It is not an absolute rule for people with lived experience and families to undergo training in existing research methods. The role of individuals with lived experience is not to have the same knowledge as professionals but to bring their “experiential knowledge” based on their real-life experiences. Without recognizing this as valid knowledge, smooth PPI implementation is impossible. Therefore, efforts to promote mutual understanding, such as aligning on the meaning of specialized terms, are essential. For example, the term “outcome” can be interpreted differently by researchers and the general public, requiring careful preparation to build a shared understanding of each term and rule.

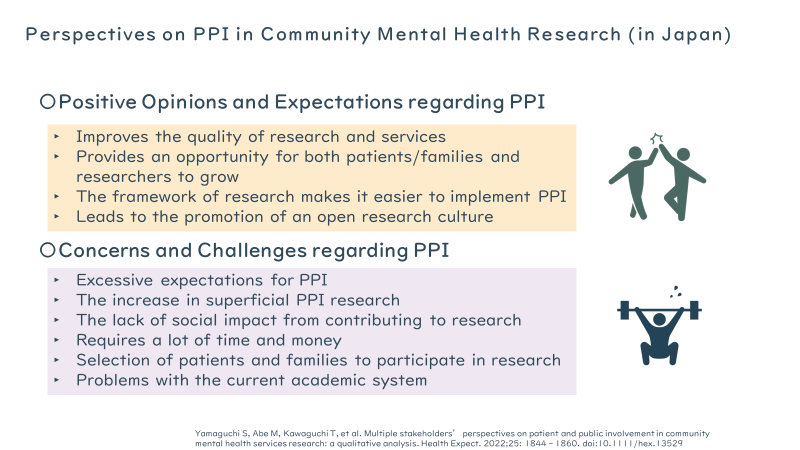

- Representativeness: The issue of “who should participate” is a constant challenge. While options exist, such as those with extensive experience in research, members of specific organizations, or randomly selected individuals, problems with representation in terms of gender, age, disability level, and economic status are always present. Since there is no single right answer, the process of who participates and how they will work together becomes crucial. In Japan, PPI in community mental health research is still in its early stages. Given the positive opinions and expectations as well as concerns and challenges (Figure 1), it is necessary to document and report the process in detail.

Figure1. Thoughts Relating to PPI in Community Mental Health (in Japan)

■ Introduction to and Achievements of the “TOGETHER Project”

The TOGETHER Project was launched in response to the increasing number of people with mental illness in Japan (over 6 million in 2020) and the shift of support from hospitals to communities as part of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s “Comprehensive Community Care System for Mental Disorders.” This shift has diversified treatment outcomes from clinical metrics, such as re-hospitalization to personal recovery outcomes that prioritize the individual, such as employment and self-realization.

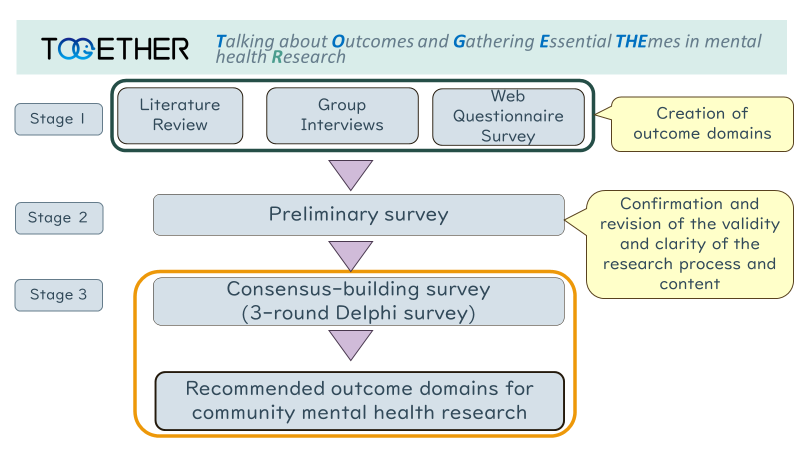

However, this diversification has also led to a lack of consistency in the outcomes evaluated across different studies. The project’s goal was to identify critical outcomes for people with mental health conditions living in communities and to determine research interests to be measured by collaborating with people from diverse backgrounds.First, approximately 1,080 outcomes were collected from literature and group interviews and then condensed into a draft of 94 outcome domains by removing duplicates. Following a preliminary survey and feedback from diverse stakeholders, the number of domains was revised to 96. In the Delphi survey, participants were asked to rate the importance of these domains on a 7-point scale and provide written comments. The research team analyzed the results, and an item was considered to have reached consensus if over 70% of the participants rated it as “important.” This process was repeated three times, with participants receiving feedback on the results before each new round.

Out of the initial 302 participants, 297 gave their consent for the study, and 291 responded to the first round, maintaining a high response rate of 98.0%. The final response rate for the three rounds was an exceptionally high 93.6%.

Figure 2: Implementation Process of the TOGETHER Project

The project’s high response rate was attributed to “research processes that prioritized PPI.” This included providing detailed explanations of the research burden during recruitment (e.g., disclosing that it would take several hours to respond to all 96 questions and that participation in all three surveys was recommended), designing a user-friendly survey website (with features like optimal font size, layout, progress bar, and a save function), diligent reminders, and providing a contact point for inquiries. These efforts were informed by comments and advice from researchers with lived experience and collaborators from diverse backgrounds during the planning phase.

As a result, 24 of the 96 outcome domains were agreed upon as important for community mental health research. The study also revealed differences in how different groups rated the importance of outcome domains. For example, 72% of participants with lived experience considered “income” to be important, while only 36% of researchers did. Conversely, 72% of researchers rated “social functioning” as highly important, while only about 50% of people with lived experience and their families did. However, the overall results showed a set of outcome domains that were considered to have a certain level of importance across all groups. This research is expected to serve as a pioneering example for the advancement of patient and public-involvement research in Japan.

■ Future Prospects and Related Projects

To determine if the 24 consented domains from the Delphi study could be considered “core outcome domains,” a consensus conference was held from fall to winter of 2024. This conference aimed to address the limitations of the Delphi method, which make it difficult to have a deep, direct discussion and explore differences in understanding. Participants from diverse backgrounds, including individuals with lived experience, families, support professionals, government officials, and researchers, re-evaluated the importance of each outcome domain through small group and full group discussions. The research team acted as facilitators, focusing on ensuring that all participants had an opportunity to express their opinions. A strict criterion was set for the final vote, where an item was designated as a core outcome domain only if over 80% of participants voted to include it. As a result, 12 of the 24 domains were selected as core outcome domains.

Future research is necessary and planned to determine the specific metrics for evaluating these 12 core outcome domains. Since various assessment tools exist in the mental health field to measure a single phenomenon, discussions among diverse stakeholders will determine if the domains can be measured with existing tools or if new methods are necessary. Information will be actively shared to ensure that the identified outcome domains are used to provide more effective support and evaluation in policymaking and daily clinical practice.

Additionally, a new project titled “Research on the Development of a Co-creation Platform in the Field of Mental Illness Research” has been introduced, funded by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED). Led by Dr. Sosei Yamaguchi of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, this project aims to develop a co-creation platform for mental illness research and create educational content for both researchers and participants. The project is expected to play a crucial role in advancing PPI in the field of mental health in Japan by addressing issues like the representativeness of participants and how each group should engage in PPI.

[Event Overview]

- Speaker:

Dr. Takuma Shiozawa (Project Assistant Professor, Department of Mental Health and Psychiatric Nursing, Graduate School of Health Care Sciences, Institute of Science Tokyo) - Date & Time: Monday, July 28, 2025, 19:00-20:15 JST

- Format: Online (Zoom webinar)

- Language: Japanese

- Participation Fee: Free

- Capacity: 500 participants

■Profile:

Takuma Shiozawa (Project Assistant Professor, Department of Mental Health and Psychiatric Nursing, Graduate School of Health Care Sciences, Institute of Science Tokyo / Research Student, Community Mental Health and Legal System Research Department, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Neurology and Psychiatry, National Institute of Neurology and Psychiatry)

After graduating from the Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health and Welfare, Tokyo Metropolitan University in 2013, he entered the graduate school of Tokyo Metropolitan University and completed his PhD. While in graduate school, he worked as a psychiatric ward nurse at Tokyo Adachi Hospital of the Kosei Kyokai Foundation, as well as a mental health counselor at Dokkyo University Health Center and a counselor at SODA, a general incorporated association, and was involved in a wide range of psychiatric treatment and community mental health support sites. In parallel with his clinical work, he has been working as a researcher at the Department of Social Reintegration Research (currently the Department of Community Mental Health and Legal System Research) at the National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry since 2017. He has been involved in policy research and practical projects related to community mental health, and has been in his current position since May 2023. His areas of expertise include community mental health, early intervention, support for young people, mental health education, and Patient and Public Involvement (PPI). He is a member of the Japanese Society for Schizophrenia Research as well as the Japanese Society of Social Psychiatry, the Japanese Society for Rehabilitation of the Mentally Disabled, the Japanese Society of Psychiatric Emergency Medicine, and the Japanese Academy of Nursing Science.

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

- [Research Report] Survey of Japanese Nursing Professionals Regarding Climate Change and Health (Final Version) (November 14, 2024)

- [Policy Recommendations] Mental Health Project: Recommendations on Three Issues in the Area of Mental Health (July 4, 2025)

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Publication Report] Planetary Health Promotion Project “Issues Facing Planetary Health and the Role of the Health Sector” (May 10, 2023)

- [Research Report] Survey of Japanese Physicians Regarding Climate Change and Health (December 3, 2023)

- [Announcement] HGPI Joins Global Green and Healthy Hospitals (August 1, 2023)

Featured Posts

-

2025-11-13

[Registration Open] (Webinar) The 1st J-PEP Seminar – Initiating Policy Advocacy from Meaningful Involvement (December 8, 2025)

![[Registration Open] (Webinar) The 1st J-PEP Seminar – Initiating Policy Advocacy from Meaningful Involvement (December 8, 2025)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/mip-ncd-20251208-top.png)

-

2025-12-01

[Policy Recommendations] Recommendations on Strategic Investments in Policies for Brain Health to Revitalize Japan: Hopes for the New Administration (December 1, 2025)

![[Policy Recommendations] Recommendations on Strategic Investments in Policies for Brain Health to Revitalize Japan: Hopes for the New Administration (December 1, 2025)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20251201_Recommendations-on-Strategic-Investments-in-Policies-for-Brain-Health.png)